The geography of the Italian deportation, by Italo Tibaldi

The geography of the Italian deportation and its various destinations

The Italian political and racial deportation to the Nazi extermination camps (22/9/1943 – 6/5/1945)

Report presented at the Conference on the System of Concentration Camps and on the Deportation

(Genoa, 29-30 November, 1 December, 2001)

by Italo Tibaldi

I wish to thank the Ligurian Institute for the History of the Resistance that has organized and strongly desired this conference, and those who have made these days dedicated to the study of the “system of concentration camps and on the deportation” possible.

I find myself here in the double role of testimony of the concentration camps experience, and as an independent and self-taught researcher on the phenomenon of the deportation in the Nazi camps and of the extermination that was its goal during the years of 1943-44-45.

“The Geography of the Italian deportation and its various destinations”: an ample and complex subject, that I will begin to analyze calling to mind the entomological significance of the word geography, as it is expressed in some of its aspects:

- human geography, in the spatial distribution of the Italian experience in the phenomenon of political and racial deportation;

- economic geography, with the utilization of human material as slaves, for the production and extraction at an intensive level in the mineral sector (mines, quarries, production of building materials), and for the war industry, as well as other sectors;

- linguistic geography, with the possibility of communication practically eliminated by the congeries of the languages specific to the concentration camps.

To proceed in this report, it was necessary to refer to several official documents that are here attached, referring to the foundation and the duration of the running of the camps:

- the classification of the camps (signed HEYDRICH), dated 2/1/1941;

- the situation of the camps and the construction of nine others, in addition to the five preexistent ones (signed POHL), dated 30/4/1942;

- the order to the commanding officer of the KZ (concentration camp) with instructions regarding the “intensive” use of human labor (signed POHL and SCHILLER), dated 30/4/1942;

- the (secret) disposition having the subject of “Numeration of the death certificates on behalf of the internal registry of the concentration camps” and the institution of a falsified numeration of the same acts (signed H.HIMMLER), dated 11/5/1943.

I will develop my report, illustrating the research that was started as far back as 1955, ten years after the Liberation, and to this day, incomplete, that is the temporary result of the attentive consultation of the traceable sources, both national and foreign, referring to the Nazi extermination camps and to the Italian political and racial deportation during the years of 1943-44-45.

The methodology chosen is that of the reconstruction of the transports, and through the history of the matriculation numbers.

It is important to know the emission dates of the matriculation numbers for all of the concentration camps, but it is even more so in those camps in which the data relative to the deportees remains incomplete.

Whenever the date of internment of a deportee is not indicated it is almost always possible to ascertain this information based upon the matriculation number which has been assigned to him.

The listing of the assigned numbers furnishes also the valuable information regarding the quantity of deportees who have passed through a particular Camp, and on the rate of sudden and massive flows of people in specific periods.

When the date of entrance in the Camp, of the individual matriculation numbers, or of the transport lists could not be ascertained with precision, it became necessary to attempt to indicate the lapse of time of the solar month in which the matriculation numbers were emitted.

It sometimes occurs that the first matriculation number of a month does not follow the last one of the preceding month, either because the missing numbers were emitted in the preceding month, or they were emitted during the month in course.

Although all of the camps were directed by a central administration, the emission of matriculation numbers did not occur in a uniform manner internally in the various camps: in some of these the matriculation numbers of the deceased or transported deportees were “recycled “, attributing them to the new arrivals.

There were some camps which reserved a series of numbers that were destined to previously announced transports of deportees; if for some reason, that particular transport arrived after it was expected, it could happen that they it was assigned a numerical series that was emitted the previous month.

In the period immediately preceding the liberation of the camps, that is, in the period of April-May 1945, the usual method of assigning numbers up until that moment could not always be followed.

It is therefore possible that the deportees that arrived during that time period did receive matriculation numbers, but on behalf of the Camp administration, the procedure of registration of these numbers was not strictly adhered to. In some cases – entire transports – the deportees coming from other camps maintained the matriculation numbers from the camp of departure.

This research has, out of necessity, been circumscribed to the camps of extermination and elimination by forced labor, of which a sufficient amount of elements relative to the Italian deportees, or those from Italy, or hailing from successive transfers to the principal camps.

During the analysis of the nominative elements, major difficulties were caused by the frequency of orthographic errors, in much the same way that there were differences to be found during the confirmation of duplicate elements appearing in several sources: for some deportees there was only partial information available, but this information was nevertheless relevant and has been indicated.

In this research of the transports, one must often attribute to the incomplete available documentation (in large part destroyed before the liberation of the Camps) the contingent and involuntary omission of names. Regarding this, I wish to at once thank anyone and everyone who could possibly signal eventual errors and inevitable imprecision.

The major task consisted in – originally – being able to retrace, through the matriculation numbers, to the restitution of the single identities, reacquiring the single identities in order to discover the journey, and the path – as completely as is possible – of their deportation, of the reasons that were behind it; and also, it was my intention to reunite those nuclear families that the deportation had dispersed.

The systematic revelation that has up to this date consented us to arrive at 40,000 matriculation numbers has however constricted the research (for the immensity of the number, and for the addition of information) to effectuating the rigorous individuation of the names of the deportees in the principal and most noteworthy Camps in historiography, proposing the single matriculations for each deportation Camp.

To permit a systematic comprehension of the material arising from the analysis of similar data coming from multiple sources, the ordering of the following sources was applied:

- the complete list (ITALIENLIST) of the political and racial deportation of Italians in the Nazi concentration and extermination camps from 22/9/1943 to 6/5/1945;

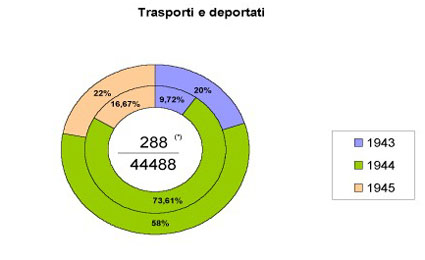

- the nominative reconstruction of 288 transports, some of these almost in their entirety, others in the process of research, in alphabetical order and with elaboration of the registration and matriculation numbers;

- the description of the transports in chronological order, beginning with the date and place of departure, the camp of arrival and the number of deportees, subdivided in the years 1943-1944-1945.

It has become necessary, also to permit a synthetic representation, to propose a series of graphs:

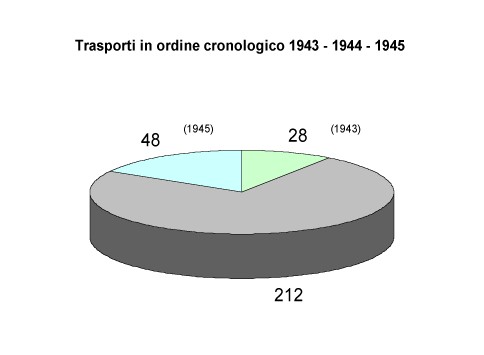

Attachment A) Graph of the transports in chronological order:1943-1944-1945

Attachment B) Graph of the relationship between transports and deportees, with relative per cents:

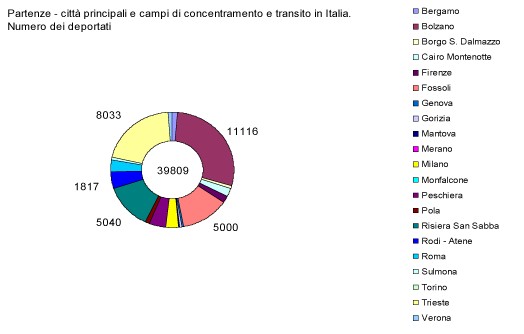

Attachment C) Graph of the departures from Italy, principal cities, of the concentration, transit and extermination camps:

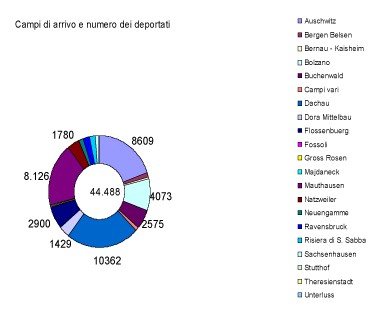

Attachment D) Graph of the camps of arrival and number of deportees:

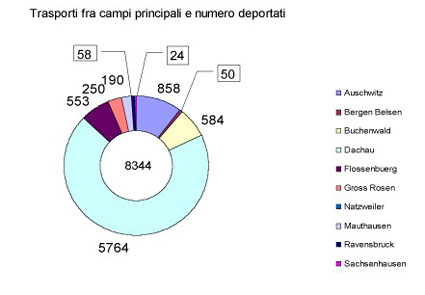

Attachment E) Graph of the transports between the principal camps and number of deportees:

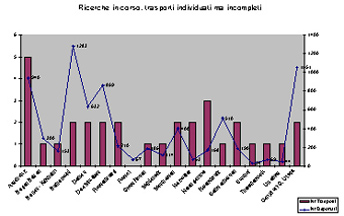

Attachment F) Graph of the individual transports, although incomplete and with research still underway:

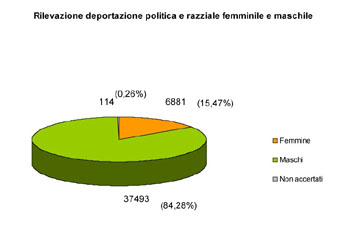

Attachment G) Graph of the political and racial deportation divided for gender:

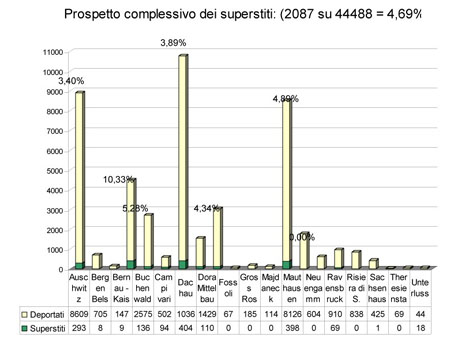

Attachment H) Graphic of the complete perspective of the survivors, with relative per cents regarding the initial deportation:

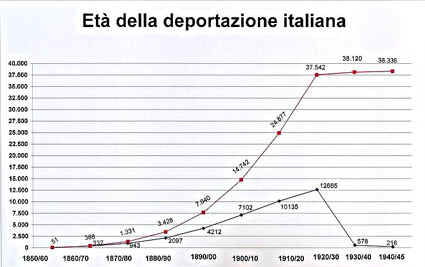

Attachment I) Analytical graphic of the date of birth organized in decades (from 1850 to 1945):

NB: the publications mentioned in points I –III, complying with the Law 675/96 and successive, and here presented, are deposited in the Archives of the ANED (National Association of Political Ex-Deportees in the Nazi camps), via Bagutta, 12 – Milan, Italy.

It must be said that the research on the transports from Italy, taking into consideration an average of 50 deportees for each boxcar, in an initial perspective of 123 transports, I have hypothesized that there were 116 boxcars utilized in 1943, 546 in 1944, 65 in 1945. A total of 727 boxcars must have been involved during that period in some railway compartments in Central Italy, and in every line in Northern Italy.

Naturally, I have requested the General Direction of the State Railways (FFSS) to interpellate for possible information regarding the journeys of those trains, certainly not rendered official. It was with responses that were substantially uncertain, for differing motivations, that the Direction had replied. Copies of these letters are attached.

I would like to include as a simple element of delineation of the Italian deportation, the elaboration of the “nominative lists of the Italian citizens hit by the measures of Nationalsocialist persecution, published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale number 130 of 11/5/1968.” (it is a listing of those who have made a request of information, and it has proved to be, in time, obviously incomplete.) Nevertheless, it contains a regional orientation – for place of birth – of the Italian population that had been deported.

Taking into account the national situation of 13,709 deportees, of whom 4,466 survivors and 9,243 deceased, the results are thus distributed:

I have also inserted a listing of the professions that were declared at the moment of entrance to the Camp, during the matriculation.

The Italian Jehovah’s Witnesses that were deported of which we have information are two.

- Narciso Riet born 30/9/1908, registered at Dachau 25/4/1944, matr. 67095, released on 7/6/44 and once again imprisoned at Dachau on 9/8/44, matr. 91186;

- Salvatore Doria born 3/10/1907, arrested 15/11/39 on indication of the OVRA for political reasons and condemned in the special court on 19/4/40 to eleven years of reclusion, deported from the penitentiary of Sulmona to Dachau on 13/10/43, matr. 56477 and 9/12/43 to Mauthausen matr. 40536.

On the indication of Matteo Pierro of the Center of Study and Documentation of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, research is underway regarding Luigi Hochreiner, born 9/2/1902, arrested and detained by the German authorities in 1940 because he was an adherent to the Association of Bible Students (Bibelforscher). His companion Helene Delacher was assassinated in 1943 for the same reasons; recently (26/2/2000) after 56 years, the Court of Justice of Vienna has passed a sentence for his rehabilitation.

At the distance of 60 years from the Shoah, it is ever more evident that history is not the same as statistics, and it can not be understood merely with averages, but it is nevertheless important to have the availability of a systematic revelation of all of the names that have been collected between the years of 1850 and 1945 (96 years). The medial age evidenced is of those born in 1914 (30/31 years old) while the largest number of individuals with the same age is of those born in 1920 (23/24 years old), having the maximum number of 1773 deportees. It emerges in evidence the Jewish deportation of 1850-1884 and 1932-1945 represented 2,852 deportees and included the elderly and children who were immediately eliminated. The forced slave labor is represented by individuals born between 1885 and 1931 and the total is of 35,484 deportees. It has not yet been possible to establish the birthdates of 6,128 deportees (of whom 1,379 were Jews.)

The Book of Memory revels that the Jews deported as political prisoners, or as civilians was 48.

To the arid, bitter, and sometimes rough concrete nature of numbers I would like to add some considerations about moments that might appear too easily dealt with, or about issues that are too quickly declared closed, or still other thoughts on passages that are not taken into enough consideration and are considered of little importance.

The graphic information isn’t intended to leave messages that are superimposed, but to give a more in depth attention, yet one that is immediate, to the real results of that experience.

After over more than half a century from the liberation, still today new documented individual testimonies are seeing the light of day. This reinforces two fundamental aspects: the statistical aspect of the population, that in daily life identifies an individual, and the matriculation number of the deportee, that distinguishes him in each concentration camp, and whenever possible, reveals some additional information that helps to reconstruct a journey. With this information, one may add to the numerical reconstruction a collective testimony, and finally to the identification of a transport, with its motivations that were political, racial or at times even both together.

Therefore, a sum of testimonies, direct and indirect, concrete in a very elementary manner, that constitute a real reading, complex in both the levels of the quantity as in the variety, serve to compose a great mosaic of over 40,000 matriculation numbers; a contribution that is unique and essential, and in any case necessary for the “History of the Deportation”.

Regarding the History and Memory of the Deportation, I share the affirmation of Paolo Momigliano, the Director of the Historical Institute of the Resistance in Valle d’Aosta. He says that “whenever one studies the Nazi extermination camps, the endiadi “history” and “memory” are made manifest with a force that is altogether particular, because the causes and the effects of the deportation and the extermination were radical and earthshaking. They were thus on an individual level, as well as a moral and cultural one, up until the level of ethics and politics”. He concludes with great regret that the research on the history of the deportation is a history that is still today suspended between “la mémoire et l’oubli” memory and forgetting.

On the Italian deportation there does not yet exist an complete historical work; there are just the historical coordinates, that here we are attempting to use to cover a hole in the systematic research of a quantitative reconstruction, one that is rigorously documented, and one that reflects the reality of the situation in an incontestable manner.

This lengthy research has permitted me to individuate the single experiences that are fused within the more immense collective tragedy.

Especially with the aid of all those who have left “testimonial writings”, urged more by the intention to pass on the memory of those who had died in noble simplicity, we have been able to trace a picture of an experience that does not limit itself to personal events or things that are related to a single group, but to be considered in the more vast sense of human values.

I could here print in its entirety the introduction and the preface written by Daniele Jallà, curator of the publication, “Compagni di Viaggio” (Travelling Companions) – the first research on the survivors of the KZ, 123 transports.

I have continually asked myself whether or not it made any sense to research on such a specialized subject as the reconstruction of the transports of the deportees to the KZ, a theme that can not be entirely related to many others, be it for its content, or be it for the message that it implies. Of course, one can’t help but ask oneself questions of this nature, especially because one finds himself in the presence of circumstances that continue to provoke thoughts of comparisons between the past and the present. Ideas which force us to continually think of the reasons behind that which was “that certain past of ours”.

With professor Enzo Collotti, we note a certain kind of historical beclouding of that which was our experience, and this translates into a weakening of the general consciousness of what Nazism really was. This research is a “work-in-progress” that wants to bear witness to the companions of deportation who in varying ways fought against Nazi-Fascism, and perhaps constitute a great, yet painful opportunity, yet one that is psychologically still very painful.

It is not the obsession of the memory, but the urgent pressure of a moral need. To compile and to pass on the lists – here attached – that are mainly death announcements, is also the result of an attentive study.

That which in “Compagni di Viaggio” seemed like a timid excursion, has assumed in these past few years the quality similar to a collective declaration of intent, and continuing with the digging into the deportation of the years 1943-1944-1945 of the Italians under the Third Reich, I have discovered over 40,000 matriculation numbers; 40,000 stories of life in the concentration camps, moments that are certainly “History” in an “Atlas that is dense with clouds”. This has caused complex and inextinguishable research. One that is made all the more difficult by the scarcity of oral sources, at this moment, there are fewer than 2,000 survivors and each one of us carries within himself his own past, one that can be another piece of the jigsaw puzzle that can still promote an ample and renewed historical and cultural reflection.

More in general, it has been made clear that the study of feminine deportation, of the Clergy in the concentration camps, of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, of the political prisoners, all used in the forced labor in the bellicose industry of the Third Reich, has never gone beyond a few specialized studies, and the destiny of all of these people has never been sufficiently investigated.

For the racial component, the Book of Memory – The Italian Jewish Deportees (1943-1945) – the important and massive work of Liliana Picciotto Fargion, with profound sensitivity of the entity of that persecution, has renewed the memory and the monitor to never forget, reassuming it all in a very incisive form.

I worked intensively for that publication, making available 8,566 nominative files in order to reconstruct the transports of the deportations of the Jews from Italy, and I wanted to add a successive in-depth study that I used to illustrate two particular aspects at the convention “Giornate di studio in ricordo di Primo Levi”, which was held at St. Vincent on 15-16 October, 1997:

-

the transportation for the deportation;

-

the reconstruction of the transport of Primo Levi and his travelling companions, according to the analytical description that comes through in “The Submerged and the Saved”, and I can not hide my enormous difficulty in attempting to overcome an emotional reading, even if I well know that there can not exist memories without emotions.

Behind the historical-scientific interest, there are the lives of 40,000 Italian deportees. The sources of that “slave trade” have been destroyed or lost and the testimonies of the survivors who are “witnesses of their time” needs a more timely insertion.

The matriculation numbers of every concentration camp roll on, incessantly, like the mouth of a great river; it is a long list of numbers that confuse, and this was precisely the intention of those who wanted to implement those numbers. Yet, after many months, with extraordinary luck and infinite suspense, we have come to the conquering our own identities.

In 45 years of research, I imagined to find a “list” of the Italian deportation without a face, and instead, the list is dense with many faces; I could never have imagined that the initial silence after the word “Deportation” would have successively found such a strong response, so credible and imposing. I can not hide the anguish that has come to meet me when uncovering certain aspects that this research hides, and that, with every passing minute, I was tempted to bring it to a halt.

Grasping to gather information, I at times found my hands empty, not one scrap of news; but then the “microchip” under the palm of my hand actually gathered everything. And now, everything unfolds with the completion of this list that has a dramatic compactness, behind the metamorphosis of the deported human, reduced to a number, there is a terrible power, the impossible attempt to “remove” that cruel vision and liberate it from any further torment.

But it is still not that way. And by now, 56 years have gone by…

The partial reconstruction of the transports of the departures and arrivals, proposed once again in this presentation as the assemblage of a mosaic where there is an overlaying of images and numbers, and it is easy to run into confusion, consents us to individuate in the geography of the Italian deportation specific situations that are object of reflections and many, many questions:

- Why were the 1,790 Italian Military Deportees from the Penitentiary of Peschiera who arrived at Dachau on 22/9/1943 assigned the qualification of Schuthaefling? These were mainly deserters, draft dodgers (today conscientious objectors) that refused to adhere to the Fascist Military (Esercito di Salò). They were imprisoned for security reasons with the red triangle (for political prisoners); and on 29 November 1943 they were then changed into the qualification of Arbeitszung-Reich, asocial prisoners assigned to forced labor in the Reich, with the attribution of the black triangle? (asocial prisoners)?

- Why did the 869 military (IMI – Internati Militari Italiani) deported to Dora-Mittelbau directly from the Balkans or to the Stammlager have the Zero (null) added to the beginning of their matriculation number?

- Why were the first four Italian political deportees who left from Trieste to arrive at Mauthausen on 30/1/1944 inserted in the transport of only males and registered together with them?

- Why were another 104 female deportees who arrived at Mauthausen on 8 April 1944 not registered, but closed in the cells of the concentration camp, transferred into the prison of Vienna and successively sent to Auschwitz and there registered on 28 September 1944? They were successively transferred to Hinterberg, commando of Mauthausen, and then registered with numbers having only two or three digits?

- Why were the 318 Italian deportees that were transferred from Auschwitz to Bergen Belsen or Ravensbrück and successively to the satellite camps of Flossenbürg given a matriculation number that was already assigned?

- Why did the 985 Italian-Slovenian deportees enclosed in the concentration camp Nr. 95 of Cairo Montenotte in the province of Savona, depending upon the Commando of Territorial Defense of Genoa, get sent directly to Gusen, a satellite camp of Mauhausen on 8 October 1943 and registered on 12 October 1943 with the numeration that was available in that camp comprised of four numbers? A large part of the deportees of that transport – described in great detail by the Slovenian historian France Filipic – died at Gusen, the other part was transferred on 24 January to the principal camp of Mauthausen and there registered once again with that same matriculation of smaller numbers? Why was another part of this group let go and successively made to “re-enter”?

- Why were the Italian priests who left from Fossoli or Bolzano not deported directly to Dachau, where following the agreements of the Holy Seat they were reserved barrack number 26? Why were those transported to Mauthausen not transferred on the first of December 1944 to Dachau with the other components of that transport? Fathers Costantino Amorth, Antonio Celli, Pietro Martini, Narciso Sordo, Antonio Rigoni, Carlo Prinetto were assigned to heavy forced labor in the Quarries of Mauthausen and Gusen or in the quarries of Melk or Ebensee and they died there. If the commanders of the camps had “obeyed the orders from the superiors”, also these clergy members would have lived the joy of the liberation of Dachau on 29 April 1945.

There are still too many unanswered questions and anomalies. Black pearls in the stormy sea of the complex geography of the deportation that still have not come to the light; certainly we will gather others. Amongst the “irregularities” I should cite the double matriculation of the same principal camp.

Among the twenty-five transports to or from Mauthausen/Auschwitz listed in the “Kalendarium” by Danuta Czech, speaking of the entrances into the KZ Auschwitz-Birkenau (1939/1945), it is evident that the transport leaving Mauthausen on 1/12/1944 and arriving at Auschwitz on 3/12 with 1,120 deportees that were specialized, non-Jews. The matriculation numbers of Auschwitz ran from 201237 to 202356. In this transport there were Italian deportees who were then once again transferred to Mauthausen on 29/1/1945 and received a second matriculation number in that camp. The research is attached.

Sometimes the vortex of the transfers is without reins. I will cite two cases:

-

that of Silvestro Laurenti, who was assigned seven matriculation numbers for seven camps

-

and that of Rosa Beretta, mechanical worker, metalworker at the Breda, fifth section, arrested at home in Monza for the strikes of 1944, not matriculated.

Another “anomaly” is certainly the bilingual manifesto in German-Italian that was posted by the German commander in the Military Piazza of Turin on 4/1/1944 with which it is announced to the population the transferring and reclusion of a “Straflager” comprised of 50 elements. Following this publication was the transport of Turin Gate. 50 deportees were taken from the prison of Nuove on 13/1/1944 and they arrived the following day at Mauhausen (I attach a copy of the manifesto and of the Transport-List that contains 45 political prisoners and 5 Jewish members of the Piemont Resistance). This is the only known case of the announcement of a transport.

* * *

These days of study on the system of the concentration camps and on the deportation are however a moment of reflection to ask us survivors, to question our sensitivity and intelligence, to those with whom we speak of the younger generations, if there is still a need of our testimonies on the direct experiences and the memories of those dramatic events, of oppression and liberation, that have characterized the “brief century”. It is well-known that for any community that does not want to relive its past, must affirm the necessity of memory.

For the “cognitivists”, human memory is a machine that elaborates information, a sort of computer that memorizes, holds and recuperates. We, survivors, have to live the past in the shoes of those who know and remember, and this has a strong emotive element, sometimes an involuntary but tenacious and obsessive recollection overtakes us: and it is never a past that fades into oblivion, losing itself in the distance.

At times it happens that we need to reconstruct a memory based upon a clue or a fragment; the mind investigates and codifies and recuperates the past (even that past that computers know nothing about) and slowly we arrive at the memory that has been lost and then found. The mind investigates and returns to the moment that this memory was our experience, a part of our lives, in that historical parenthesis.

In these long years, our memories as witnesses have become memories of history itself, constructed by those who have transformed our experience with oral or written communication, and with study. This memory belongs to historical events that are not confined to the closed box of a now faraway past, but they can still today influence the present, project us into the future, with the value and the meaning of an experience that can not be locked away or removed to the shadows of oblivion.

Certainly, scholars, professors, passionate researchers with the spirit of the truth have come to us and have known how to awaken us to a more mature knowledge of our role: “the duty to testify, always”, encouraging us to not stay anchored to a static memory or one limited to saying, “I was there”.

We are not the only ones, nor are we the privileged bearers of the identity of that portion of the national community that was deported to the concentration camps, and we do not claim the exclusive status of those who suffered and were persecuted, nor do we support victimization. We wish to reflect together, intent upon communicating with whomever wants to know and interpret our memories and the capacity to transmit them to be able to create a great historical fresco that has the indisputable force of its complexity.

It is not our wish that our memories are read as a new page, underlined with a pencil over a line that has remained dotted up until today.

Memory is the only weapon we have at our disposition. It is a response that is ever relevant and immediate to the “doubtful”, to those who easily forget; it is a page that is intensely open to who makes the euphemistic hypothesis of “modifying the dimensions” of that memory and our actual history.

But we, escaped from being neutral, will not die in silence. We will testify with tenacity the roots of the truth, of the negated humanity of the concentration camps, for the memory of what they were and for our history.

In memory of the many companions who did not have the fortune to return, leaving in the concentration camps their lives dense with hopes, I will cite two who, all too soon, concluded their lives in those places:

-

RICHARD SILBERSTEIN (son of Walter and Edith Hahn, born in Vienna, Jewish residents in Florence, held in the camp of Fossoli on 20 January 1944 and deported in the camp of Auschwitz on 16/5/1944, deceased in unknown place and date) born in the concentration camp of Fossoli at Carpi on 29 March 1944, he too, deported on 16 May 1944 to Auschwitz, and killed upon arrival, 23 May 1944.

-

DANILO KOZMANN, son of Giovanni and Savina Rupel, political deportee to Ravensbrück on 6 December 1944 (n° 91329), born at Ravensbrück Wednesday 14 February 1945, at Block 32 (the block of pregnant women), died on 28 February 1945. “There was a matriculation number on his little hand, a sort of tape with a number; even babies had to respond to the roll call”. They defined him as a “Kleine partizan”.

Italo TIBALDI

Publications and sources (Italian and foreign):

- 1947 – Primo Levi “Se questo è un uomo” Ed. F. de Silva

- 1948 – Le crimes allemands en Pologne, Vol. I

-

1950 – Catalogue of Camps and Prisons in Germany and German-occupied Territories (Settembre 1939 – May 1945) I e II volume (I.T.S. AROLSEN)

- 1951 – i d e m III Volume (I.T.S. AROLSEN)

- 1954 – Piero Caleffi “Si fa presto a dire fame” Ed. Avanti

- 1960 – Piero Caleffi e Albe Steiner “Pensaci, Uomo!” Ed. Feltrinelli

- 1962 – Enzo Collotti “La germania nazista. Dalla repubblica di Weimer al crollo del Reich Hitleriano” Ed. Einaudi

- 1962 – Domenico Tarizzo “Ideologia della morte” Ed. Il Saggiatore

- 1965 – Haeftlings-Nummernzuteilung im Konzentrationslager (I.T.S. AROLSEN)

- 1965 – Valeria Morelli “I deportati.italiani nei campi nazisti” Ed. Scuole Grafiche Artigianelli

- 1965 – Vincenzo Pappalettera “Tu passerai per il camino” Ed. Mursia

- 1968 – Gaz. Ufficiale nr. 130 Elenchi nominativi cittadini italiani deportati

- 1976 – Bruno Bettelheim “Il prezzo della vita” Ed. Adelphi

- 1976 – Paul Berben Histoire du Camp de Concentration de Dachau (1933-1945)

- 1977 – Bundesgesetzblatt nr. 64 Verzeichnis der Koncentrationslager und ihrer Auesenkommandos

- 1978 – Lidia Rolfi Beccaria e Anna Maria Bruzzone “Le donne di Ravensbrueck” Ed. Enaudi

- 1979 – Luciano Happacher “Il lago di Bolzano” Artigrafiche Saturnia

- 1981 – Bruno Bettelheim “Sopravvivere” Ed. Feltrinelli

- 1981 – Alberto Cavaglion “Nella notte straniera” Ed. Franco Angeli

- 1982 – Bundesgesetzblatt nr. 82 – Aenderung und Ergaenzung des Verzeichnisses der Konzentrationslager und ihrer Aussenkommandos

- 1984 – Flavio Fabbroni – “La deportazione dal Friuli nei campi di sterminio nazisti” Ist. Friulano per la storia del movimento di liberazione

- 1985 – Andrea Devoto “Il comportamento umano in condizioni estreme” Ed. Franco Angeli

- 1986 – Federico Cerea e Bruno Mantelli “La deportazione nei campi di sterminio nazisti” Ed. Franco Angeli

- 1986 – Anna Bravo e Daniele Jallà “La vita offesa” Ed Franco Angeli.

- 1986 – Primo Levi “I sommersi e i salvati” Ed. G. Einaudi

- 1988 – Giovanni Malodia “Di là da quel cancello” Ed. Mursia

- 1988 – Adolfo Scalpelli “San Sabba: istruttoria e processo per il Lager della Risiera” Ed. Mondadori

- 1989 – Alberto Berti “Viaggio nel pianeta nazista” Ed. Franco Angeli

- 1989 – Danuta Czech “Kalendarium der Ereignisse im Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau 1939-1945”

- 1991 – Ulrich Bauche, Heinz Bruedigam, Ludwig Eiber e Wolfgang Wiedey Hrsg ” Arbeit und Vernichtung: das Konzentrationslager Neuengamme 1938-1945″

- 1991 – Liliana Piciotto Fargion “Il libro della memoria – Gli Ebrei deportati dall’ Italia 1943-1945” Ed. Mursia

- 1993 – Gustavo Ottolenghi “La mappa dell’ Inferno – tutti i luoghi di detenzione nazisti 1933 – 1945” Ed. Sugarco

- 1994 – Anna Bravo e Daniele Jallà “Una misura onesta” Ed. Franco Angeli

- 1994 – Italo Tibaldi “Compagni di viaggio” Ed. Franco Angeli

- 1994 – Marco Coslovich “I percorsi della sopravvivenza” Ed. Mursia

- 1995 – Giovanna Massariello Merzagora e Paolo Massariello “Le donne di Ravensbrueck : 600 nomi per ricordare” Bollettino della società letteraria di Verona nr. 9 bis

- 1996 – Enzo Collotti e Lutz Klinkhammer “Il fascismo e l’ Italia in guerra” Ed. Ediesse

- 1996 – EDV – Erhebungsprojekt der KZ-Gedenkstaette Mittelbau-Dora “Italienische Haeftlinge im KZ Mittelbau-Dora 1943-1945”

- 1997 – Andreas Baumgartner “Die vergessenen Frauen von Mauthausen”

- 1997 – Marco Coslovich “Racconti dal Lager” Ed. Mursia

- 1997 – Teo Ducci “Bibbliografia della deportazione nei campi nazisti” Ed. Mursia

- 1997 – National Archirv College Park – Maryland U.S.A. – Dr. A. Schmidt / Archives II textual ref. Branch – Captured German and related records on microform in the National Arhives.

- 1998 – France Filipic “Slovenci V Mauthausnu” Ed Cabkarjeva zalozba –Liubliana

- 1998 – Hans Brenner “Frauen in den Aussenlagern des K – Flossenbuerg”

-

1999 – Hans Marsalek “Mauthausen” “La storia del campo di concentramento di Mauthausen.” Ed. Oesterreichsche Lagergemeinschaft

-

Legge nr. 404 (06/02/1963); Legge nr. 792 (18/11/1980); Legge nr. 94 (29/1/1994).

Relations with the international committees and museum directors/camp archivists that have aided in the research:

- Dr. Kurt HACKER (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di AUSCHWITZ;

Dr. Pierre DURAND (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di BUCHENWALD;

Gen. André DELPECH (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di DACHAU;

Dr. Pierre DURAND (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di DORA-MITTELBAU;

Walter BECK (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di MAUTHAUSEN;

Robert PINCON (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di NEUENGAMME;

Dr.ssa Annette CHALUT (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di RAVENSBRUECK;

Pierre GAUFFAULT (Presidente) Comitato Internazionale di SACHSENHAUSEN;

Dr. Henry WROBLENSKI (Direttore) del Memorial, Museo Internazionale di AUSCHWITZ;

Dr. Wolkhardt KNIGGE (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette BUCHENWALD;

Dr.ssa Barbara DISTEL (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette DACHAU;

Dr.ssa Cornelia KLOSE (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette DORA-MITTELBAU;

Dr. Raymond FLUCK (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette NATZWEILER-STUTTHOF;

Dr. Detlef GARBE (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette NEUENGAMME;

Dr.ssa Sigrid JACOBEIT (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette RAVENSBRUECK;

Dr. Gunther MORSCH (Direttore) del Memorial KZ-Gedenkstaette SACHSENHAUSEN;

Mag. Andreas BAUMGARTNER (Direttore) del Memorial Gedenkstaette MAUTHAUSEN;

Dr. Wolf SZYMANSKI, Dr. Willi SOUCEK Bundesministerium fuer Inneres der Oesterreichischen Republik

Joerg SKRIEBELEIT KZ-Gedenkstaette FLOSSENBUERG;

Dr. Thomas RAHE KZ-Gedenkstaette BERGEN BELSEN.

- Computerized optimization and graphics – Valeriano Zanderigo

- Translation of documents – Eralda Caserio